Editor's Note: This extensive technical piece on NIST’s mistreatment of the WTC 7 evidence is broken down into a series of five articles. The fourth installment (Part 4) is presented below.

Introduction

Part 1: NIST and Popular Mechanics Fabricate Myth About WTC 7's "Scooped-Out" 10 Stories

Part 2: Fictitious Gouge Launches Design Flaw Myth and Collapse Initiation Fantasy

Part 3: Trusses & Tanks — Popular Mechanics Helps NIST Create More Myths

Part 4: Independent Analysis Disproves NIST’s New Thermal Expansion Hypothesis

Part 5: How Skyscrapers Are Really Imploded

In 2008, the final report on World Trade Center Building 7 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) abandoned two myths that the 2005 Popular Mechanics article had misleadingly presented as the foundation of the official explanation for WTC 7's destruction. The first myth it discarded was the sensational story about the non-existent 10-story gouge. The second myth was about a non-existent seven-hour-long diesel fuel fire.

Instead, NIST's final report correctly acknowledged that the building endured normal office fires, none of which persisted more than 30 minutes in any given location.

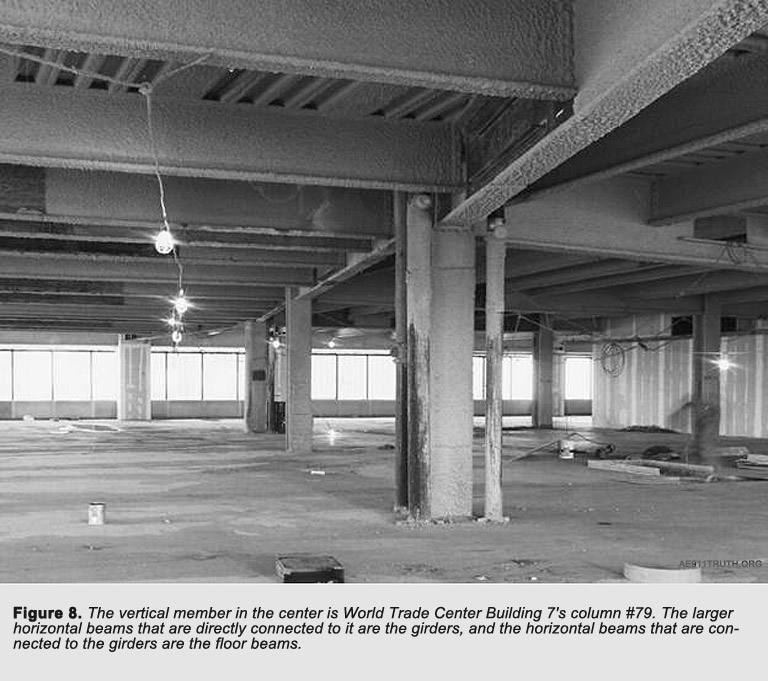

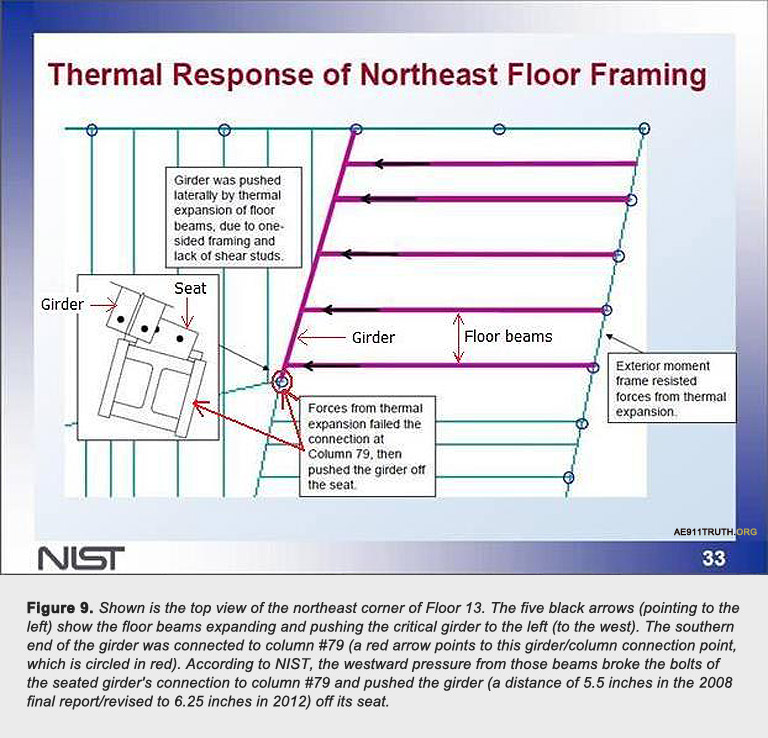

Nevertheless, NIST insisted that WTC 7 was the first steel-framed skyscraper in history to be leveled by normal office fires (NCSTAR 1A, p. 47 [PDF p. 89] and NCSTAR 1-9, Vol. 2, p. 604 [PDF p. 266]). NIST had invented a new mundane explanation for how the equally mundane fires had heated up and expanded the floor beams, which in turn had caused a critical girder to "walk off" of its seat. According to this new hypothetical scenario, a fire in the northeast section (near column #79) of Floor 12 heated the beams of the floor above it, causing them to expand a few inches, and then . . .

- the expanded floor beams pushed a single horizontal girder sideways 6.25 inches, which . . .

- caused the girder to fall off the seat that connected it to vertical column #79, which . . .

- resulted in the collapse of the northeast corner of Floor 13, which . . .

- set in motion a cascade of falling floors in the area, which . . .

- left several floors of column #79 without lateral support, which . . .

- led to the buckling of column 79, which . . .

- led to the horizontal failure of all the interior columns and then the failure of all the exterior columns which . . .

- brought about the symmetrical sub-seven-second collapse of the whole building, including . . .

- 2.25 seconds of collapse in free-fall acceleration.

NIST's claim that a 6.25-inch shift of one girder could trigger the implosion of Building 7 is nothing short of remarkable. Can a sub-seven-inch movement of one girder really trigger a sub-seven-second destruction of a 47-story steel-framed skyscraper? Many scientists and other critical thinkers doubt it, and would like to see evidence to back up such a wild claim. They want to know, in short, whether NIST's final explanation of WTC 7's destruction is any more credible than the original fantasies presented in the infamous 2005 article by Popular Mechanics. Let us find out.

NIST's new magical thermal expansion hypothesis is plagued by a plethora of problems. We will list only some of the most obvious ones here. NIST based its work entirely on a computer simulation that was supposed to simulate the design of WTC 7 and its condition on that fateful day. But the alleged simulation was instead based on numerous false premises that were either not backed by any evidence or contradicted available evidence. In other words, NIST had once again inverted the scientific method in order to arrive at its preconceived conclusion.

Below are 10 of these false premises:

False Premise #1. The allegation of a Floor 12 fire after 5:00 PM

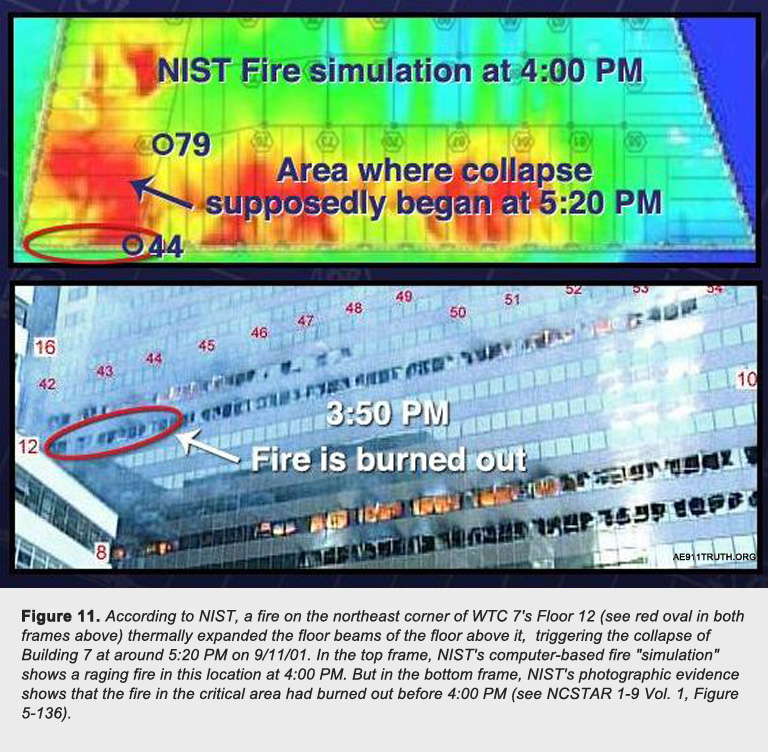

NIST's new thermal expansion hypothesis would have needed evidence for a Floor 12 fire in the vicinity of column #79 after 5:00 PM, according the NFPA 921 (see Figure 10). Why? Because Building 7 collapsed at approximately 5:20 PM on September 11, 2001 — and NIST's explanation for that collapse was based on the assumption of a fire raging in that location. Yet NIST had no evidence for this alleged post-5:00 PM fire. Indeed, its photographic data (see Figure 11) demonstrated that the fire in this area had already burned out prior to 4:00 PM. This is especially significant, because NIST had already admitted that Building 7 suffered normal office fires that lasted less than 30 minutes in each location before burning out — once the fuel (office furniture) had been exhausted — and moving on. Thus, judging by NIST's own data, another fire after 5 o'clock in that same location would have been impossible, because there was nothing left there to burn.

False Premise #2. The claim that shear studs failed due to "differential expansion"

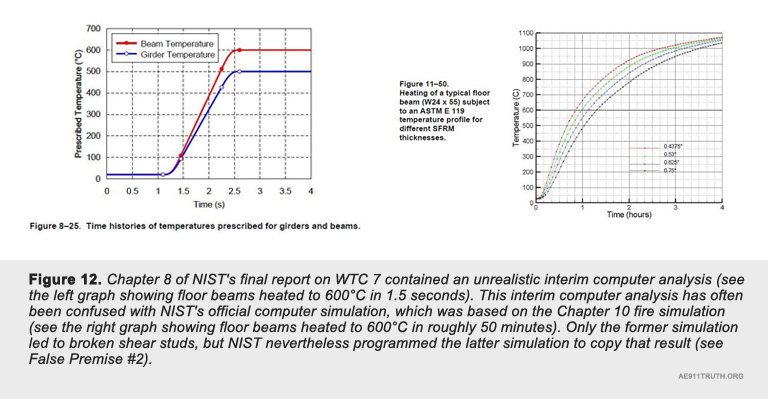

The steel floor beams and the concrete floor slab that rested on them were made into one composite unit via the shear studs that were welded to the beams and encased in the cement. The alleged thermal expansion of the floor beams would not have been able to push the girder independently of the floor slab unless these shear studs had failed. Thus the NFPA 921 would have required evidence for this failure, but NIST had no valid evidence to suggest this failure was likely — or even possible. NIST did show shear stud failure in an interim analysis in Chapter 8, but it was invalid for two main reasons:

1) This supposed analysis was in fact a separate computer simulation (see Figure 12) that had been deceptively programmed to artificially induce the "differential expansion" phenomenon that resulted in broken shear studs. It showed the steel floor beams heated up to the maximum temperature while the concrete floor slab remained unheated — which would be impossible in the real world. Thus, the Chapter 8 model showed the maximum possible thermal expansion of the floor beams while simultaneously showing zero expansion of the slab. This trick maximized the different expansion rates (called "the differential expansion") of the beams and the slab. In other words, the model showed the shear studs breaking at the junction between the beams and the slab, because it had been manipulated to show the floor beams lengthening while the slab remained stationary.

2) NIST's official computer model that allegedly simulated the Building 7 collapse was based on its official fire simulation, shown in Chapter 10 (see Figure 12). Since this fire simulation was meant to be realistic, it had not been programmed to artificially keep the floor slab cold — which meant no computer model based on that simulation could show broken floor shear studs. In fact, NIST never repeated its Chapter 8 shear stud failure analysis with the Chapter 10 fire simulation data, which means NIST never had any evidence to support its assumption of broken shear studs. Nevertheless, NIST programmed its Building 7 "computer simulation" to take broken shear studs for granted.

False Premise #3. The insinuation that girder shear studs were missing

The girder most likely had shear studs that joined it to the concrete floor slab. These shear studs would have prevented expanding beams from pushing the girder off the seat plate. NIST's 2004 preliminary report even acknowledged the existence of the shear studs — perhaps because its collapse theory at the time did not rest on the notion that the shear studs had purportedly not been in place. Four years later, though, the final report made some subtle text modifications, which made the shear studs magically disappear. Structural engineer Ron Brookman M.S., S.E, has found fabrication and construction aspects for this particular girder that show 30 shear studs. He has also found structural drawings that show 30 shear studs on this girder on other floors. NIST has essentially insinuated that the shear studs either were not installed or were installed only on some floors. Both suggestions are extremely unlikely at best, and, more importantly, not supported by the NFPA 921 requirement for evidence: NIST has refused to release the "as built" drawings to prove it was justified in ignoring these shear studs in its 2008 report.

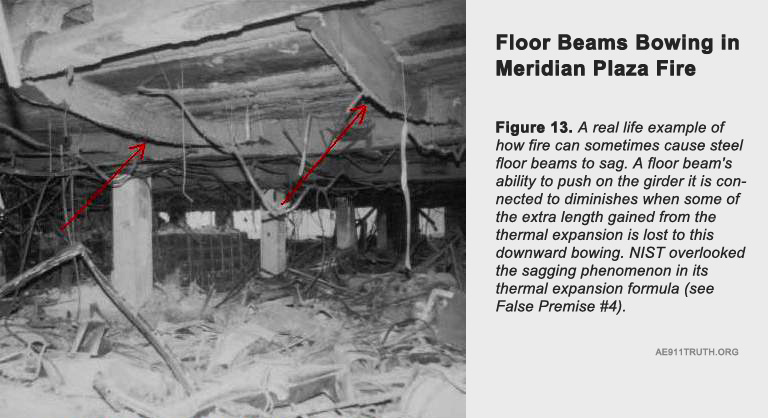

False Premise #4. The overlooking of beam sag in its calculations

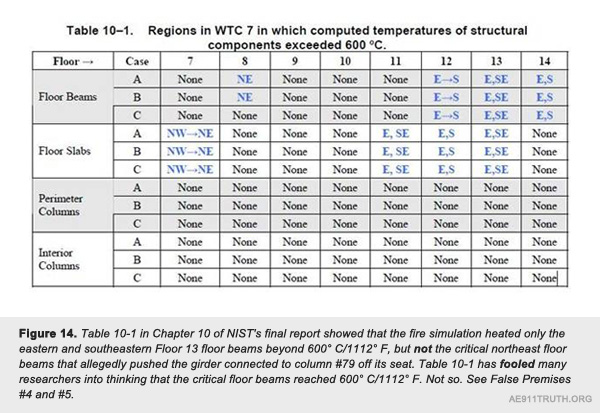

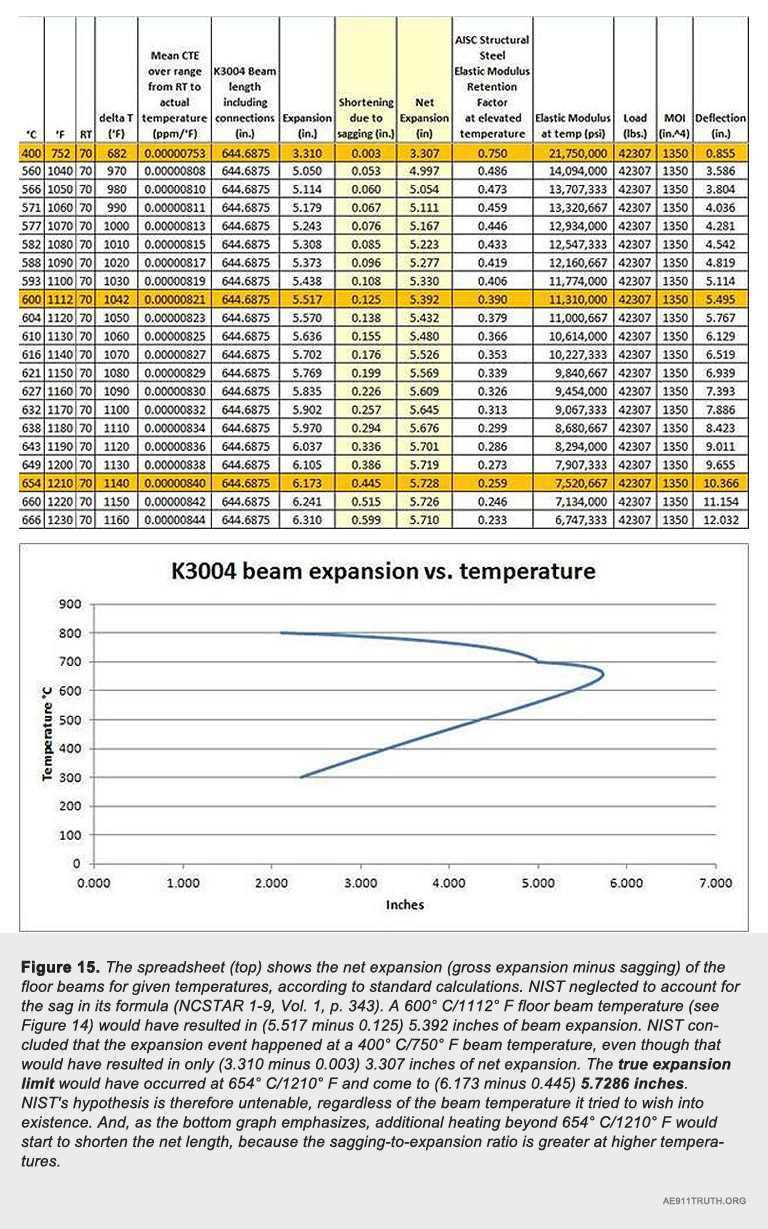

NIST's fire simulation (Chapter 10 of the final report) concluded that the fire did not heat the critical floor beams beyond 600° C/1112° F (see Figure 14). By saying that, NIST was suggesting that these beams had been heated to 600° C/1112° F. This is a crucial point, because when NIST apparently plugged this maximum temperature into its thermal expansion formula (see NCSTAR 1-9, Vol. 1, p. 343), the result was a maximum possible floor beam expansion of just over 5.5 inches. Thus, the original thermal expansion hypothesis (in the 2008 final report draft) appeared valid, because it was based on the erroneous notion that 5.5 inches would suffice to push that girder off its seat plate. But independent analysis in April 2012 (revised in December 2014) by professional mechanical engineer Tony Szamboti has demonstrated that the actual net expansion at 600° C/1112° F would have been less than 5.4 inches (see Figure 15) due to beam sagging (see Figure 13). Did NIST purposely overlook the sagging factor in order to achieve a targeted 5.5-inch expansion?

False Premise #5. The setting of an impossibly high floor beam temperature

"The thermal analysis in Chapter 10 determined the temperature of structural members when subjected to the gas temperatures from the FDS analysis, but it did not account for thermally-induced damage. During the ANSYS analysis of structural response, structural members or their connections may have failed before reaching the temperatures shown in Chapter 10." — Footnote, NCSTAR 1-9, Vol. 2, p. 494

In Chapter 11 of its final report, NIST buried a stunning admission in a footnote, which revealed that Chapter 10 had neglected to mention that the thermal expansion hypothesis could not be based on a 600° C/1112° F floor beam temperature (see quoted NIST footnote above). The Chapter 11 summary (NCSTAR 1-9, Vol. 2, p. 536) went on to conclude that the floor beams pushed the girder between columns 79 and 44 off its seat at column #79 prior to the beam temperature reaching 400°C. But NIST did not reveal the implication this lower beam temperature had for its thermal expansion hypothesis: As Figure 15 demonstrates, this lower beam temperature would have limited the floor beam expansion to about 3.3 inches, which would have proved NIST's original hypothesis untenable. Remember, the original hypothesis needed the 5.5 inches of expansion (caused by the higher 600° C/1112° F temperature) to pan out. The NFPA 921, had it been followed, would have forced NIST to list calculations to prove that the floor beam expansion could have reached the 5.5-inch target. NIST, however, did not address that basic scientific requirement.

False Premise #6. An incorrectly assumed 11-inch seat plate width

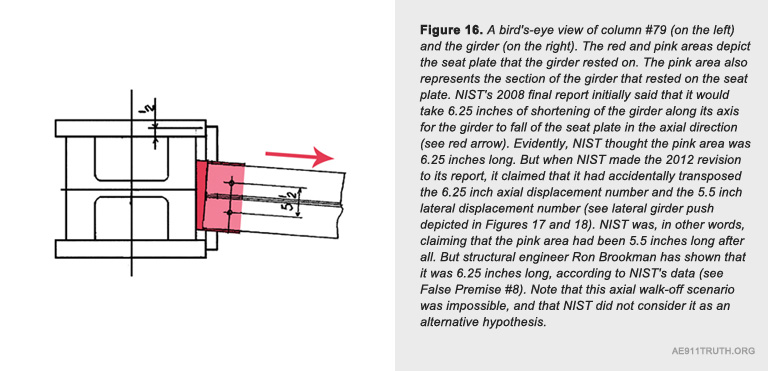

In June 2012, NIST quietly stretched the alleged expansion displacement from 5.5 inches to 6.25 inches. Why the change four years after its final report on WTC 7? It turns out that a small team of independent researchers had proved that the seat plate had been 12 inches wide (not 11 inches, as previously thought). NIST had assumed that the required expansion distance equaled half the width of the seat plate — the distance from the center of the seat plate (where the girder rested) to its edge. The corrected width of the seat plate changed this number from 5.5 inches to 6.0 inches, which meant NIST's 5.5-inch expansion limit had never been sufficient to cover the distance. Why did NIST change the number to 6.25 inches instead of 6.0 inches? To find out, see the next false premise.

False Premise #7. The revised 6.25-inch expansion number still insufficient

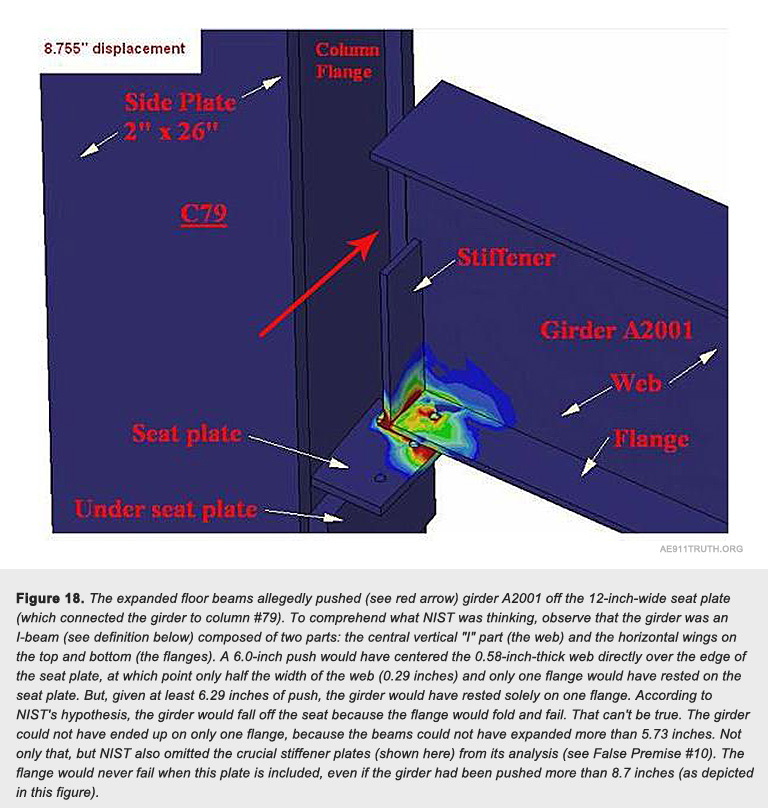

When NIST decided on its original 5.5-inch expansion requirement, it had neglected to take into account the 0.58-inch center section of the girder, called the web. Had it considered the web, NIST would've added half its thickness, or 0.29 inches, to the thermal expansion requirement (see Figure 18). So the initial required expansion distance would have been (5.5 plus 0.29) 5.79 inches. Then, with the correct seat plate width, it would have been (6.0 plus 0.29) 6.29-inches. NIST's revised 6.25 inches of claimed expansion distance didn't quite reach the required 6.29 inches, though, and was therefore technically insufficient to satisfy the most basic premise of the thermal expansion hypothesis. That fact, however, was the least troubling part of the revision. What was the most troubling? See the next false premise.

False Premise #8. The thermal expansion limit was exceeded

As we have already discussed, the NFPA 921 scientific method would not have allowed NIST to claim that the girder walked off its seat once it had been pushed laterally a certain distance, unless NIST were able to prove that the floor beams could have pushed the girder that far. When NIST revised its hypothesis in 2012 from 5.5 to 6.25 inches as the target lateral displacement number, it did not explain how it could exceed its own 5.5-inch expansion limit. And as the caption of Figure 15 explains, NIST could not have backed up its new 6.25-inch number, because the maximum possible thermal expansion of that beam length would have been about 5.73 inches, regardless of the beam temperature. NIST's excuse for its revision? It claimed that the 5.5-inch figure had been a typing error, where NIST had accidentally transposed the 5.5-inch lateral displacement number and the 6.25-inch axial number. But as Figure 16 demonstrates, that explanation does not add up. Structural engineer Ron Brookman has confirmed that NIST's original identification of the axial walk-off displacement as 6.25 inches was correct. Curiously, NIST also insisted that it had actually been basing its computer simulation on the "correct" 6.25-inch lateral distance all along. That innocent-sounding assertion might seem reasonable — until, that is, one realizes that this would mean that NIST had consciously based its hypothesis on an expansion distance that was physically impossible according to its own data. A more blatant violation of the NFPA 921 would not be possible.

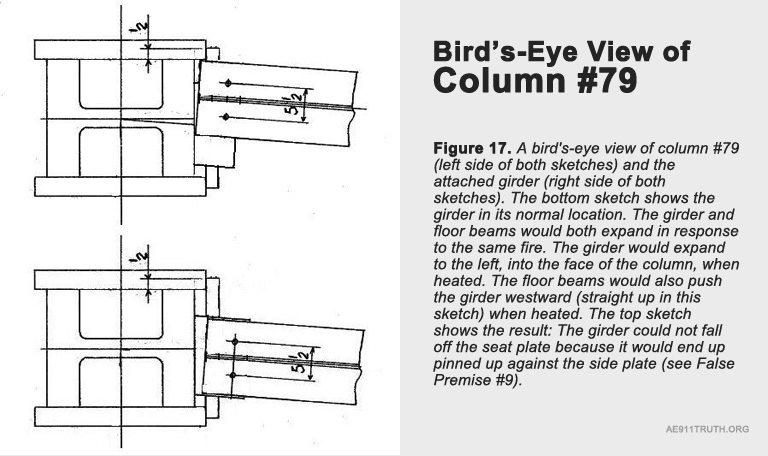

False Premise #9. An assumption of unobstructed girder movement

NIST's fire simulation in Chapter 10 showed the girder heating up along with the floor beams, though to a lesser extent than the floor beams. Indeed, both in the simulation and in real life, the girder would have expanded along with the floor beams. An expanded girder would have pressed up against the face of column #79 — and, more importantly, against the side plate on the western side of the column. This side plate would have prevented the girder from being pushed more than 3.2 inches to the west, and therefore would have prevented the girder from falling off the seat plate (see Figure 17). NIST had encountered this problem in the computer analysis shown in Chapter 8 of the final report, but it did not mention or address it in later chapters that featured the thermal expansion hypothesis. The NFPA 921 scientific method would have forced NIST to address this issue.

False Premise #10. The non-inclusion of critical stiffener plates

At no time did NIST reveal the fact that the girder flanges had stiffener plates (see Figure 18). These plates would have prevented the failure of the flange, even if thermal expansion numbers had vastly exceeded the already-impossible 6.25-inch movement. The presence of the stiffener plates alone invalidates NIST's thermal expansion hypothesis, even if one overlooks all of its other false premises. NIST has responded by claiming that including these plates was unnecessary, because they were designed to stiffen the web, not to stiffen the flanges. But Figure 18 shows that these plates obviously strengthened the flanges as well, since they were on the flanges at the end of the girder, directly over the seat plate. In its evasive answer, NIST didn't attempt to challenge this fact.

I-beam definition: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-beam

Part 4 Discussion and Conclusion

The NFPA 921 scientific method specifically mandates that a theory be based on "facts that can be proven clearly by observation or experiment." But NIST's methodology violated this scientific methodology every step of the way to such a degree that NIST actually inverted the scientific method. It concocted a fairytale based on a collection of assumptions that were either not backed by any evidence or were in conflict with the available evidence. NIST's farfetched story was based on a fire that could not have existed according to its own data. Moreover, NIST had no proof that this fire, even if it had existed, could have led to broken shear studs on the floor beams. Consequently, NIST had no proof that those particular floor beams could in theory have thermally expanded and pushed that girder off its seated connection. It therefore had no scientific reason to waste time and money on the thermal expansion hypothesis. Yet NIST kept this charade going with a lot of suspicious errors, omissions, and distortions.

For example, in hindsight, it is clear that NIST's original 5.5-inch expansion hypothesis (made prior to its June 2012 revision to 6.25 inches) required the combination of several of the errors listed in this article in order to appear valid. Specifically, NIST (1) incorrectly measured the seat plate as 11 inches wide, (2) did not account for the 0.58-inch-thick web, and (3) omitted the stiffener plates, to come up with the artificially low 5.5-inch expansion distance that was allegedly needed to push the girder off its seat. Also, we notice that (4) NIST's initial — and incorrect — assumption of a possible 600° C/1112° F floor beam temperature just happened to yield the 5.5-inch floor beam expansion target, thanks to (5) a thermal expansion formula that neglected to subtract the loss of net floor beam expansion due to beam sagging, thus barely yielding the 5.5 inches of expansion NIST sought to prove.

This collection of errors, in other words, quite conveniently conspired to let NIST know that it needed 5.5 inches of expansion and that it did in fact have 5.5 inches of expansion.

Yet these aspects of NIST's suspicious methodology are minor compared to some of its other, more serious omissions and distortions, which also raise questions about potential scientific misconduct.

For instance, why did NIST refuse to release the "as built" drawing for the girder sheer studs? Would it reveal that the girder shear studs were actually there, as designed? Why else would NIST want to hide it?

Then there is the unscientific and suspicious switcheroo that NIST pulled with its computer simulation in Chapter 8, which gave the impression that the actual fire simulation in Chapter 10 could have led to broken floor shear studs. Did NIST choose to not repeat the Chapter 8 simulation with the real fire simulation data because it knew that it would not show the shear stud failure? Or did NIST in fact do the experiment, then not publish the result, because it showed no broken shear studs?

We may never know. The only thing we do know for sure is that NIST did not show any analysis proving that the actual fire simulation could lead to broken shear studs, even though its thermal expansion hypothesis would stand or fall on that one point alone.

When NIST decided to cherry-pick this one result from the Chapter 8 simulation, it meanwhile completely ignored the fact that this simulation indicated that the thermal expansion hypothesis could not work out, given that the side plate prevented the girder from being pushed off the western side. NIST should have pointed out that potential problem and addressed it, but instead it did not even mention it.

It should be noted that the interim experiment shown in Chapter 8 has caused a lot of confusion, because it led to a scenario where the floor beams buckled and pulled the critical girder backwards off of its column #79 seated connection, causing it to "rock off" the seat in the eastern direction (instead of being pushed forward off the seat in the western direction). Some have erroneously treated this scenario as a potential alternative to the thermal expansion hypothesis. However, it was no more than an artifact produced when the Chapter 8 shear-stud-failure model was allowed to run its course.

In addition, we have to question the mentality that NIST displayed when it neglected to mention and address the problem with its Chapter 11 conclusion. The thermal expansion hypothesis was flimsy enough when NIST was entertaining a potential 600° C/1112° F floor beam temperature and the consequent 5.5-inch expansion potential. The hypothesis was physically impossible, however, with NIST's much lower 400° C/750° F floor beam temperature, which would have limited the expansion potential to about 3.3 inches. NIST needed almost 2 more inches of expansion to validate its hypothesis, but it saw no reason to even mention that problem.

NIST showed equally perplexing behavior when it revised its hypothesis in 2012 to specify the alleged expansion distance as 6.25 inches instead of 5.5 inches, even though it had previously identified 5.5 inches as the expansion limit. Again, NIST saw no reason to mention that problem, let alone address it.

Simply put, NIST's official computer simulation could not possibly have shown the floor beams expanding and pushing the girder more than about 3.3 inches. Both 5.5 inches and 6.25 inches were off limits. NIST's computer simulation could therefore not possibly have shown the girder falling off its seat — even though NIST says it did.

Would you like to verify NIST's assertion with your own eyes? Well, you can't. Instead, NIST asks you to accept its word.

In the end, NIST's inability to prove that the 6.25-inch floor beam expansion would have been possible is not the main issue, considering that it omitted the crucial stiffener plates that would have rendered the alleged 6.25-inch expansion irrelevant. Had NIST included these plates, its thermal expansion hypothesis would have required almost 9 inches of beam expansion to pan out, which would quite obviously have been impossible. Did NIST exclude these plates from its analysis to save its hypothesis or did it have a legitimate reason for doing so? We find it impossible to believe NIST's claim that its engineers determined that those plates would not strengthen the flanges at all, and that they could therefore justifiably omit them. NIST cited no documents to back up this bold claim.

The NFPA 921 scientific method would not approve of NIST's thermal expansion hypothesis without proof from NIST that the floor beams could expand 6.25 inches and that the girder — with the stiffener plates in place — would then fall off its seat. Again, rather than showing any proof, NIST asks us to just accept its word.

So, do you think all this smacks of a deliberate effort to come up with data to support a preconceived conclusion? If NIST had intended to honestly explore the ramifications of a fire in that critical region of the building, it would have discarded the thermal expansion hypothesis once it became apparent that the presence of shear studs, the low temperature of the floor beams, the side plate restriction, and the stiffener plates each led to a dead end.

We cannot learn the full extent of the computer model fudging unless NIST allows independent verification of its alleged computer simulation. But this agency of the US Department of Commerce has refused to release crucial model input data, explaining that doing so "might jeopardize public safety." Translation: Apparently NIST believes that the data could get into the wrong hands and aid terrorists in bringing down more skyscrapers. That is absurd reasoning, since NIST has already given terrorists the message that normal random office fires can implode skyscrapers. Perhaps NIST's real concern is that independent scrutiny of its methodology would destroy its reputation for professional integrity?

That this government body has disregarded serious professional critiques that challenge its conclusions has not gone unnoticed. In fact, every time NIST's sanctimonious attitude is exposed, more building experts and scientists discover that its reports cannot be trusted, and they join the 9/11 Truth community in calling for a real, truly scientific investigation. Indeed, NIST's lack of professional integrity may be AE911Truth's best recruitment tool.

In the next (fifth) installment of this series, Part 5: How Skyscrapers Are Really Imploded, the authors explore whether or not NIST's overall explanation for the total collapse of Building 7 was plausible, and review some of the controlled demolition evidence that NIST ignored.